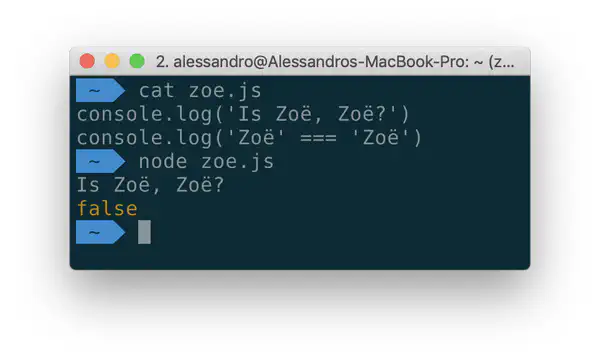

Sooner or later, this hits every developer:

This is not another one of JavaScript’s oddities, and I could have shown you the very same result with code in almost every other programming language, including Python, Go, and even shell scripts.

It first hit me many years ago, when I was building an app (in Objective-C) that imported a list of people from a user’s address book and social media graph, and filtered out duplicates. In certain situations, I would see the same person added twice because the names wouldn’t compare as equal strings.

In fact, while the two strings above look identical on screen, the way they’re represented on disk, the bytes saved in the file, are different. In the first “Zoë”, the ë character (e with umlaut) was represented a single Unicode code point, while in the second case it was in the decomposed form. If you’re dealing with Unicode strings in your application, you need to take into account that characters could be represented in multiple ways.

How we got to emojis: a brief explanation of character encoding

Computers work with bytes, which are just numbers. In order to be able to represent text, we are mapping each character to a specific number, and have conventions for how display them.

The first of such conventions, or character encodings, was ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange). It used 7 bit and could represent a total of 128 characters, including the Latin alphabet (both uppercase and lowercase), digits and basic punctuation symbols. It also included a bunch of “non-printable” characters, such as newline, tab, carriage return, etc. In the ASCII standard, for example, the letter M (uppercase m) is encoded as number 77 (4D in hex).

The problem is that 128 characters might be enough to represent all the characters English-speakers normally use, but it’s orders of magnitude too small to represent every character of every script worldwide, including emojis. 😫

The solution was to adopt a standard called Unicode, aiming to include every single character of every modern and historic script, plus a variety of symbols. Unicode 12.0 was released just a few days ago, and includes over 137,000 characters.

Unicode can be implemented in multiple character encoding standards. The most common ones are UTF-8 and UTF-16; on the web, UTF-8 is significantly more popular.

UTF-8 uses between 1 and 4 bytes to represent all characters. It’s a superset of ASCII, so the first 128 characters are identical to those in the ASCII table. On the other hand, UTF-16 uses between 2 and 4 bytes.

Why use both? Western languages typically are most efficiently encoded with UTF-8 (since most characters would be represented with 1 byte only), while Asian languages can usually produce smaller files when using UTF-16 as encoding.

Unicode code points and character encoding

Each character in the Unicode standard is assigned an identification number, or code point. For example, the dog emoji 🐶 has the code point U+1F436.

When encoded, the dog emoji can be represented in multiple byte sequences:

- UTF-8: 4 bytes,

0xF0 0x9F 0x90 0xB6 - UTF-16: 4 bytes,

0xD83D 0xDC36

In a JavaScript source file, the following three statements print the same result, filling your console with lots of puppies:

// This just includes the byte sequence on the file

console.log('🐶') // => 🐶

// This uses the Unicode code point (ES2015 and newer)

console.log('\u{1F436}') // => 🐶

// This uses the UTF-16 representation, with the two code units (each of 2 bytes)

console.log('\uD83D\uDC36') // => 🐶

Most JavaScript interpreters (including Node.js and modern browsers) use UTF-16 internally. Which means that the dog emoji is stored using two UTF-16 code units (of 16 bits each). So, this should not surprise you:

console.log('🐶'.length) // => 2

Combining characters

This brings us back to our characters appearing identical, but having different representations.

Some of the characters in the Unicode charset are combining characters, intended to modify other characters. For example:

n + ˜ = ñu + ¨ = üe + ´ = é

Not all combining characters add diacritics. For example, ligatures permit joining ae into æ, or ffi into ffi.

The problem is that some of these characters could be represented in multiple ways.

For example, the letter é could be represented using either:

- A single code point U+00E9

- The combination of the letter

eand the acute accent, for a total of two code points: U+0065 and U+0301

The two characters look the same, but do not compare as equal, and the strings have different lengths. In JavaScript:

console.log('\u00e9') // => é

console.log('\u0065\u0301') // => é

console.log('\u00e9' == '\u0065\u0301') // => false

console.log('\u00e9'.length) // => 1

console.log('\u0065\u0301'.length) // => 2

This can cause unexpected bugs, such as records not found in a database, passwords mismatching letting users unable to authenticate, etc.

Normalizing strings

Thankfully, there’s an easy solution, which is normalizing the string into the “canonical form”.

There are four standard normalization forms:

NFC: Normalization Form Canonical CompositionNFD: Normalization Form Canonical DecompositionNFKC: Normalization Form Compatibility CompositionNFKD: Normalization Form Compatibility Decomposition

The most common one is NFC, which means that first all characters are decomposed, and then all combining sequences are re-composed in a specific order as defined by the standard. You can choose whatever form you’d like, as long as you’re consistent, so the same input always leads to the same result.

JavaScript has been offering a built-in String.prototype.normalize([form]) method since ES2015 (previously known as ES6), which is now available in Node.js and all modern web browsers. The form argument is the string identifier of the normalization form to use, defaulting to 'NFC'.

Going back to the previous example, but this time normalizing the string:

const str = '\u0065\u0301'

console.log(str == '\u00e9') // => false

const normalized = str.normalize('NFC')

console.log(normalized == '\u00e9') // => true

console.log(normalized.length) // => 1

TL;DR

In short, if you’re building a web application and you’re accepting input from users, you should always normalize it to a canonical form in Unicode.

With JavaScript, you can use the String.prototype.normalize() method, which is built-in since ES2015.