Update June 2020: This blog is not served through IPFS anymore.

Fun fact: if you’re reading this article, you’re using the distributed web. Since mid-February 2019, this blog, With Blue Ink, has been served through IPFS and the Cloudflare Distributed Web Gateway.

Last November I blogged about how to run a static website from IPFS. I was already running a couple of apps in that way used by myself and my family, and I felt it was time to migrate my blog too. This took a bit longer than expected as I dealt with some issues, some of them explained below, but around a month ago I flipped the (DNS) switch and definitively turned off the single-instance VM that was hosting the blog.

That decision made me anxious at the moment, but a month in things look almost entirely good.

The Hacker News + Reddit effect that wasn’t

Since migrating to IPFS, something happened.

Just over a week ago, I published a blog post around the importance of normalizing Unicode strings, which went almost viral, peaking at #4 on the front page of Hacker News and gaining the top spot of r/programming, and was included in some popular newsletters. (Thanks for the love and for the great discussions!)

Then, on Monday I released Hereditas, a new open source project which got a pretty good exposure on Reddit too.

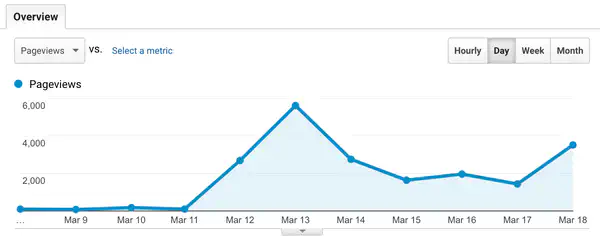

For a blog that used to average less than 3,000 page views per month, this happened:

On Wednesday, March 13, traffic was 5,060% higher than on the same day a week earlier. In a single day, With Blue Ink got almost double the page views than in an typical month before that.

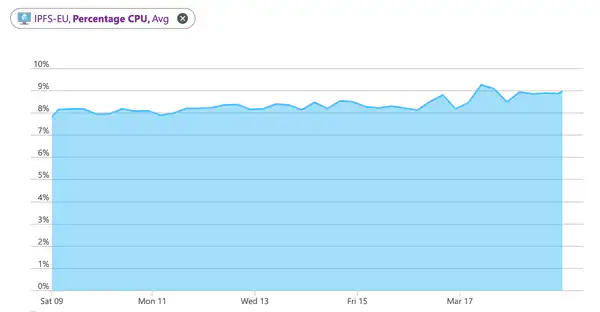

Despite the significant increase on traffic, here’s what happened to the CPU usage of one of the main IPFS nodes serving the website:

Nothing.

Thanks to distributing the content via IPFS, and serving it via the Cloudflare CDN, With Blue Ink saw virtually no impact on performance and availability following a 5,000% traffic spike.

Not just that: tests show the website has been incredibly fast for users all around the world, consistently.

Meet Hugo

With Blue Ink is a static website. I write the content in a bunch of Markdown files, and then generate the HTML pages using Hugo. The entire website (content, theme, scripts) is open source and it’s published on GitHub at ItalyPaleAle/WithBlueInk.

When I started this blog in three years ago, I had originally chosen Jekyll, another popular static site generator. However, as I was working on the migration to IPFS, I had to replace Jekyll with Hugo, because Jekyll doesn’t support relative URLs. With Jekyll, all generated URLs start with / or a fixed base URL, and this can’t work when you’re browsing the content via IPFS where the base URL is dynamic (see my previous IPFS guide for details on why this matters).

Migrating to Hugo brought some other great benefits. Hugo is a small app written in Go, and it’s much, much faster than Jekyll, which is a Ruby gem. Not only Hugo is speedier at building the website (really, it feels almost instant), but thanks to being a single, self-contained binary it also installs much faster in a CI environment. My CI builds went from over five minutes to less than one. Also, Hugo has a lot of powerful, interesting features, and it’s actively maintained.

Meet IPFS

The InterPlanetary File System, or IPFS, is a protocol and network that distributes immutable content in a peer-to-peer fashion.

If you’re not familiar with IPFS, think of it as a distributed CDN. Once you start an IPFS node, you can use that to publish documents on the IPFS network, and other people around the world can request them from you directly. The best thing is that as soon as someone requests a file from you, they immediately start seeding it to others. This means that when using IPFS, the more popular a document is, the more it’s replicated, and so the faster it is for others to download it.

Distributing files through IPFS can be very fast and very resilient. Thanks to being distributed and peer-to-peer, the IPFS network is resistant to censorship and DDoS attacks.

Additionally, all documents on IPFS are addressed by the hash of their content, so they’re also tamper-proof: if someone were to change a single bit in a file, the whole hash would change, and so the address would be different.

The problem with IPFS is that it’s just a content distribution protocol, not a storage service. It’s more akin to a CDN than a NAS. I still need some servers, and I currently have three, configured in a cluster with IPFS Cluster. They’re small, inexpensive B1ms VMs (1 vCPU, 2 GB RAM) on Azure, running in three different regions around the world. You can read how I set them up in the previous article.

Thanks to using IPFS, this simple and relatively inexpensive solution is able to deliver “100%” uptime and is DDoS-resistant. The websites are automatically replicated across all nodes in the cluster which start seeding them right away, and with the VMs geographically distributed users get great speeds all around the world.

Let’s see the architecture

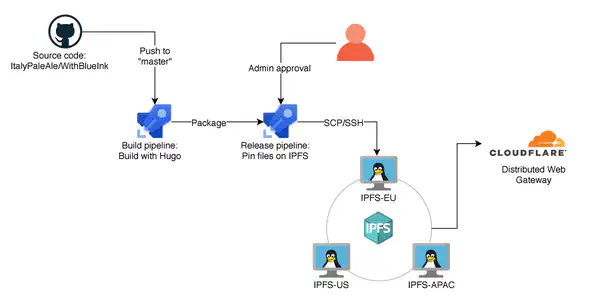

The architecture of the blog is relatively simple:

Pushing some new code to the master branch on GitHub triggers an automatic build in Azure Pipelines, which clones the source code and runs Hugo to build the website (it’s all free!). You can see the configuration in the azure-pipelines.yaml file inside the repo.

After the build is done, Azure Pipelines triggers an automatic release job. The release pipeline has two stages (you can read how I configured them in the other IPFS article):

- Copy the files into one of the IPFS VMs, then via SSH invoking the

ipfs-cluster-ctl pin addcommand to add the documents to the cluster and replicate them across all nodes. - Make a REST call to the Cloudflare APIs to update the DNSLink, which is a TXT DNS record

_dnslink.withblue.inkcontaining the IPFS hash of the website.

While the first stage happens automatically, there’s a gate requiring manual approval by an administrator (me!) before stage two can run. This lets me test and make sure that the website is loading successfully via IPFS (using its full hash) before making it available to anyone visiting withblue.ink.

After the release pipeline is done, anyone running an IPFS daemon can visit the website at this IPFS address:

/ipns/withblue.ink

This is simple and easy to remember. But it only works for those who have an IPFS daemon running, or know how to use a gateway (e.g. try it with gateway.ipfs.io).

If you’re curious to try IPFS, the ipfs-companion extensions for Firefox and Chrome lets you browse the IPFS network easily, with an external gateway or a built-in one.

Most users are still using HTTP and a normal web browser, and that’s when Cloudflare comes to assistance. With their (free) Distributed Web Gateway, edge nodes in the Cloudflare network can act as IPFS gateways and serve documents published via the IPFS network. Set up is very simple and if Cloudflare manages your DNS, thanks to CNAME flattening you can use root domains too (such as withblue.ink without www)!

Learnings from real-worldexperience

I’ve been serving web apps through IPFS for six months, and this blog for over a month. Overall, I’ve had a positive experience, but I’ve learnt a few things worth sharing if you’re looking at using IPFS yourself.

What is going well

In general, relying on IPFS has delivered some interesting benefits.

- “100%” uptime for the documents through the IPFS network. As long as there’s at least one peer who is serving the content because it has recently viewed the website (any kind of clients), or has pinned it (my three servers), the blog is reachable through IPFS.

- Speed: the more users visit the website through IPFS, the faster it becomes for everyone else.

- The website should also be DDoS-resistant in a natural way.

In reality, however, most users don’t access this blog through IPFS, but instead they visit it over HTTP(S) through the Cloudflare gateway. This has still worked fairly well:

- Since each document in IPFS is immutable, Cloudflare is caching the website extensively in each edge node around the world. There’s no need for the CDN to connect to the upstream server to check for new content for as long as the DNSLink is the same. Latency tests from multiple locations worldwide show consistent, speedy page load times. When your blog’s front page fully loads (including images) in around 3 seconds with a fresh cache more or less consistently from every corner of the planet, it’s quite impressive.

- Setting things up is really simple. Besides pointing the CNAME to the Cloudflare gateway and asking them to enable the TLS certificate for my domain, things just work. No need to configure high-availbility, load-balancing, replicating the content across multiple servers, etc.

- The Cloudflare CDN also does amazing things for you, including supporting HTTPS and HTTP/2.0 (SPDY!), gzipping responses, etc.

What I learnt / could go better

HTTP turned thirty years old this month, while IPFS is still a new technology. With IPFS, some things work differently than we’re used to, and others just don’t work at all.

- IPFS isn’t serverless; it’s also definitely not free. You do need at least one server seeding your data. The good news is that you don’t need large servers. A burstable 1-core VM offers more than enough CPU; if you’re running IPFS Cluster too, however, you do need 2 GB of memory. Adding three nodes like I did was probably an overkill (but a great learning experience–and really fun).

- All URLs in your website must be relative. I’ve explained this in details in the previous article I wrote on IPFS. In short, because users can visit your website from multiple base URLs (in my case,

https://withblue.ink/,https://<gateway>/ipns/withblue.inkorhttps://<gateway>/ipfs/<ipfs-hash>), you can’t use absolute URLs in your HTML pages. This was also the main reason why I had to switch from Jekyll to Hugo. - As I wrote above, most users don’t browse the website through IPFS directly, but rather through Cloudflare. This means that our actual uptime depends on theirs. While Cloudflare has been working just fine so far for me, they don’t offer an SLA for their free service, and it’s even less clear if there’s an SLA for the IPFS gateway. Sadly, I don’t have data on how many visitors use IPFS at the moment, but I’d expect them to be a tiny minority.

- When using the Cloudflare IPFS gateway, certain things aren’t available, including:

- No ability to set custom HTTP headers. This can be a problem in two cases: when you want to enable HSTS (there’s simply no way to do that), and when you want to manually set the

Content-Type(IPFS gateways determine the content type from the file extension and using some heuristics, see this issue). - No custom 404 pages.

- No server-side analytics, not even through Cloudflare. Your only option is to use hosted solutions like Google Analytics.

- No ability to set custom HTTP headers. This can be a problem in two cases: when you want to enable HSTS (there’s simply no way to do that), and when you want to manually set the

- Another issue I’ve noticed is that the Cloudflare IPFS gateway doesn’t always, reliably purge the cache when you change the value of your DNSLink. It can take hours for everyone to see the most up-to-date content. This has been the biggest issue I’ve had so far.

- After updating the DNSLink value, there can be a bit of a cold start time issue, with the first pages taking an extra few seconds to load, but in my experience it’s not too bad. This happens because the IPFS client in the Cloudflare gateway needs to traverse the DHT to find which nodes are serving your content. As soon as the content is replicated, this becomes faster and faster, to the point it’s not an issue anymore.

- Lastly, one issue I’ve experienced with running an IPFS node is that it can use quite a bit of bandwidth, just for making the network work (not even for serving your content!). This has been greatly mitigated with IPFS 0.4.19, but my Azure VMs are still measuring around 160GB/month of outbound traffic (it was over 400 GB with IPFS 0.4.18).

Many of the issues above, including with caching, cold-start time, server-side analytics, custom HTTP headers and 404 pages, could be mitigated by implementing a custom IPFS gateway, rather than relying on Cloudflare’s. This is what the official ipfs.io website does too; it’s something I’m considering if the issue with caching on Cloudflare doesn’t improve.