History has a tendency to repeat itself.

I built my first website in 1999, using some of the most advanced technologies available to webmasters (I can’t really use the word developers in this case) at the time: WYSIWYG editors. For me (and for many, many others!) that originally meant Microsoft FrontPage—and I’m telling you this with an awkward smile on my face of both nostalgia and shame. My websites were a bunch of static HTML pages with enough JavaScript and flashy GIFs that were screaming 2000-era Internet, and were served by static hosters that were essentially the Italian equivalent of Geocities. In the next years I graduated to better options, like Macromedia Dreamweaver MX (now Adobe), which was released in 2002; its biggest advantage was that the code it generated was much more standards-compliant.

Ten years later, in 2009 I was still building websites, but the key word back then was dynamic. All pages were server-side generated, using PHP. Not just PHP: developers were building full-stack web apps in .NET, Java, Python, Ruby… These technologies weren’t exactly new: ASP had been around since 1996, and PHP first appeared in 1994! However, it was in the second half of the 00’s that those technologies became accessible to many more small teams and individual developers, fueled by new frameworks that simplified web development: for example, Django and Ruby on Rails came out in 2005. Additionally, around those years we started seeing really cheap hosting options for dynamic sites (shared hosters like Bluehost, which was founded in 2003), so developers didn’t have to manage their own servers. Cloud computing was still a relatively new thing at the time, and it was mostly Infrastructure-as-a-Service anyways.

Fast forward to present times. It’s 2019, and developers are now… building static sites once again. You might call this a case of Nietzschean eternal recurrence applied to web development. This time, however, things are different: web browsers are significantly more capable than they were 20 years ago, thanks to newer HTML, JavaScript and CSS standards and APIs. We can build incredibly complex applications that run within a web browser, from spreadsheets to 3D games, and we don’t need to rely on external plugins. (We’re also back to using a very large number of GIFs, but this time we’re doing it ironically!)

The JAMstack and the isolated frontend

The first draft of HTML5 was published in 2008, and browser vendors have been constantly implementing new web standards and adding APIs to the web since then. From more “basic” things, such as the <video> tag that contributed greatly to the demise of Adobe Flash, to proposed foundational changes to the way we build the web like WebAssembly, developers often have a hard time staying on top of what’s new and possible.

One of the biggest advancements, however, was in the popularization of a new design paradigm for web apps, which has been dubbed JAMstack: JavaScript, reusable APIs and pre-rendered Markup. Taking inspiration from mobile apps, the idea is that even web apps should have the frontend tier completely isolated from the backend one, communicating only over HTTPS via a set of agreed-upon interfaces.

The JavaScript part of the JAMstack should be quite self-evident: the entire application runs in the client, which is a web browser, and it’s powered by JavaScript (you can also interpret this definition more broadly as in pointing to the same VM in the browser that executes JavaScript code, so to include WebAssembly too).

The “A” is definitely the most interesting part, referring to APIs: they’re what makes JAMstack apps interactive and enable great experiences for end-users. Your static app can interact with other services via APIs that are invoked over HTTPS. The simplest examples are RESTful APIs, which are easy to build and to consume. More recently, GraphQL has been gaining popularity, and it’s particularly useful for data that can be represented by graphs (it’s no coincidence it was invented at Facebook). For certain scenarios, such as apps that need to exchange significant amounts of structured data, protocol buffers and gRPC are another option, although they require a proxy to work with web browsers at the moment. Lastly, real-time apps might leverage WebSocket. You’re free to choose whatever API format you want, for as long as it suits your needs.

Speaking of APIs, one very important detail is that they could belong to anyone. Your app might be interacting with APIs that you (or your backend team) built and maintain. Or, you might be using third-party APIs, such as those offered by SaaS applications. We’ll focus on those more later on.

Lastly, the “M” is JAMstack is for pre-rendered Markup. Web apps are static HTML files, that are pre-rendered at “build-time” by various bundling tools such as webpack, Parcel or Rollup). There can also be content rendered from Markdown files, like what static site generators do, for example Hugo, Gatsby and Jekyll. All the pre-processing is done on a developer’s machine or on a Continuous Integration (CI) server, before the apps are deployed.

Apps that are written using the JAMstack are, once “compiled”, just a bunch of HTML, JavaScript and CSS files, with all accompanying assets (images, attachments, etc). There’s no server-side processing, at any time. This gives JAMstack apps significant benefits.

First, JAMstack apps are incredibly easy to deploy, scale, and operate, and can have exceptional performance. You can deliver your static files from a cloud object storage service (such as Azure Blob Storage or AWS S3), which are insanely cheap (pennies per GB stored each month) and highly redundant and reliable. You also don’t need to manage and patch servers or frameworks when you use object storage services, so that’s less overhead and more security. When you then place a CDN (Content Delivery Network) in front of your object storage, you get your website served and cached directly by multiple end-nodes around the world, with minimal latency for all your visitors worldwide and incredible scalability. If you feel inclined, you can also serve your files through the Inter-Planetary File System (IPFS), as I’ve done.

Second, the developer experience (DX) for JAMstack is a breeze. For a starter, frontend developers and backend ones can each focus on their own code, and as long as they agree on the interfaces and APIs, they can operate essentially autonomously. Gone are the days of monolithical apps with often complex templating engines (remember PHP?), that caused conflicts and headaches for both teams. Since frontend apps are eventually just a bunch of static files after they’re “compiled”, they’re also easy to deploy, atomically: at a high level, you copy the new bundle to your storage area and then update the CDN to point to the new assets. “Compilation” for frontend apps tends to be really fast, and there’s no need to worry about containerization and container orchestration, Kubernetes, etc. Given how standardized the tools are, setting up a Continuous Integration and Continuous Delivery (CI/CD) pipeline is usually simple thanks to pre-made templates. Lastly, frontend developers are able to experiment freely, and in some cases they could even point development frontends to production backends.

It’s all about speed

The real benefits for end-users are apps that feel fast. Not only this increases user satisfaction, but also engagement and retention rates of your users.

There are three sides to explain why apps feel fast. First, the app itself loads the data asynchronously, so users can see the interface while the data is loading, and can interact with it. Take a look at the GIF of the new Twitter app loading:

The app itself loads almost instantly. It then gradually begins requesting data asynchronously, and it populates all sections of the interface.

The second reason is that the ability to cache the app extensively. For many JAMstack apps, the JavaScript and CSS files don’t change frequently, so clients can cache them for a long time after downloading them. This saves time to request the app’s code, so clients need to fetch the data only. Additionally, if the web app is served through a CDN, it allows users to retrieve your code from an end node located close to them, greatly reducing latency. Even though the app’s code might be many KB’s in size, the reduced latency in downloading it from a CDN and the ability to cache the files locally mean that apps are actually faster.

With regards to caching, you can also use some more technologies like Service Workers to implement caching of your app’s code and (some of) the data, to speed up page load further, and even offer an offline experience.

Lastly, the API server doesn’t need to spend time generating and serving full HTML pages, and it just responds with the raw data (usually, a JSON payload, compressed with gzip in transit), letting the client do the work of building the page. When you have your assets inside an object storage service, the backend server doesn’t receive all the requests for static assets, so it has more resources to work on the actual business logic and APIs.

You might not need your own APIs

I wrote above that the “A” in JAMstack stands for APIs, and that you can use any API, built and operated by anyone.

You can authenticate users with external identity providers. If you’re building an enterprise app, chances are your directory is already inside (or synchronized with) Azure AD or the G Suite Directory. For consumer apps, look into login with social providers such as Apple, Facebook, GitHub, etc. There are also companies like Auth0 and Okta that offer powerful, extensible solutions, including account management (sign-up forms, password reset…) and integration with various external providers. The nice thing is that many other APIs can support authentication tokens from at least some of the providers above, so you get instant integrations. Plus, using external identity providers rather than rolling your own authentication code is a good idea regardless, as it’s the safest thing to do.

There’s then the plethora of SaaS services you can integrate with, that can give your app access to insanely vast amount of data and capabilities without any effort on your end.

There are APIs for weather and traffic, displaying stock prices and maps, monitoring flights, and even ordering pizza delivery. You can measure the traffic of a website using Google Analytics or Adobe Analytics. If you’re building a blog, letting users comment on your post is easy with services like Disqus or Commento.

If you ever need a CMS to easily, dynamically modifying the content of the website, you have multiple options among “headless content management systems”. For example, Strapi and Ghost. Even the ubiquitous WordPress can be used in headless mode.

For an enterprise application, integrating with office suites like Microsoft Office 365 and G Suite lets you send and receive emails, manage calendars and contacts, create documents and spreadsheets, access enterprise directories, and much more. These services also come with cloud storage in OneDrive and Google Drive, so you can easily use those to store and retrieve data.

Developers can also rely on external services for things like: accepting credit card payments (Stripe), converting between file formats and generating thumbnails for images (for example CloudConvert), processing videos, sending messages (e.g. through Slack, Teams, Twilio, etc)… The list is endless. Some database services can be accessed directly from frontend applications, like Firestore.

Lastly, you can also leverage some “low-code/no-code” services for all the processing that absolutely needs to happen in a server environment, for example because they need to connect services that cannot be accessed by clients directly (databases, certain Enterprise applications, etc). One of those solutions is Azure Logic Apps, which is essentially an IFTTT for developers and enterprises, and you can trigger it via a REST call.

The benefits of using APIs offered by external services are hard to miss. It’s someone else’s responsibility to ensure that they’re available and scale as needed. You don’t need to patch any application or framework, let alone the infrastructure, and they’re maintained by a team of individuals that guarantees their security too.

There can also be some interesting benefits with regards to privacy and compliance : if your app is only on the client-side and doesn’t store any data, the burden of GDPR compliance is for the most part on the service providers you rely on, just like using external services for payments like Stripe frees you from having to adhere to PCI-DSS.

Of course, you can also resort to building your own APIs when you have no other option. With serverless platforms like AWS Lambda and Azure Functions you don’t need to manage and scale your own servers, although you’re still responsible for some things, such as patching your application, ensuring that it runs on a supported runtime (e.g. target an updated Node.js version when the one you were using reached end of life), and optionally considering how to geo-replicate the deployments and load balance across those. Building your own APIs often requires managing your datastores too, that need to be replicated, backed up, scaled.

What could be next: the “JEMstack”

Building web apps with the JAMstack, relying on our own APIs and/or third-party ones, is among the most advanced design patterns in web development today. After decades spent moving apps into servers, full-stack, and taking as much of the work away from the client as possible, we’re back into putting more tasks into browsers.

There’s only one part that still requires servers, whether yours or someone else’s: the APIs. The logical next question to ask, then, is how can we get away from servers entirely?

An answer could eventually come from using blockchains, in particular Ethereum.

I propose we call this “JEMstack”, acronym for JavaScript, Ethereum and pre-rendered Markup. This stack would be part of the “web 3.0”, or the distributed web. Your “JEMstack” distributed apps (or, dapps) will be served through IPFS, and their data will be stored within a blockchain, as a distributed ledger. Some of the benefits include giving back to users control over their data, and letting developers not having to worry about any infrastructure whatsoever.

We’re not quite there yet. You can totally build dapps using blockchains, especially Ethereum, and in fact there’s a number of them out there already: a nice, curated list is on App.co. However, there are still many things that need to be solved before such technology can become mainstream.

The developer experience (DX) with building Ethereum-based apps is actually really good. Apps can easily access and mutate data stored on the blockchain with simple, seamless invocations of smart contracts. Such smart contracts are made of code that is compiled for and runs on top of the Ethereum blockchain (technically speaking, the Ethereum Virtual Machine). Smart contracts can store data and perform computations on it, and they’re usually written using a C-like language called Solidity.

However, as I’m writing this, the end-user experience (UX) has still lots of room for improvement, and this is the biggest obstacle to broad dapp adoption and it will likely be for a while longer.

To start, most users will need to install browser extensions to interact with Ethereum, such as Metamask for Firefox and Chrome, and Tokenary for Safari. Only lesser-popular browsers like Brave and Opera offer built-in support for Ethereum wallets. Mobile is another minefield, where users need to download special apps like Coinbase Wallet or Opera Mobile to interact with blockchains.

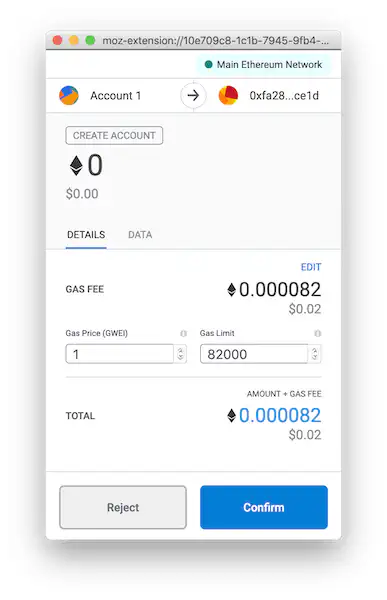

Then, users have to deal with Ethereum wallets. While reading data from Ethereum is free and simple (and requires no interaction from users), writing anything on the blockchain requires manual approval from users and payment of at least a “gas fee”. That’s a fraction of Ethereum tokens that users need to pay to be able to execute code that mutates the state of the blockchain, and it is required regardless of whether the smart contract’s function itself is payable (ie. it transfers funds—Ethers—to someone else). The UX is not delightful, requiring users to explicit click on a popup, and then waiting seconds to minutes for transactions to be confirmed by the Ethereum blockchain. And, of course, users need to first have purchased Ethereum tokens, something that’s not as simple as it might seem, especially in some countries around the world. Lastly, there are security concerns if users misplace their wallets’ private keys or restore words, or aren’t careful enough with them.

Confirmation popups are a common part of the Metamask UX

There’s a vast community that is working on improving the UX for blockchain applications, making it easier to add identities, building more transparent processes, making transactions faster or even instant, etc. As with every technology still in a fluid state, there are various competing blockchain technologies, and just as many different platforms and frameworks. I expect that we’ll see more convergence and standardization in the next months and years, and eventually dapps written on the “JEMstack” might become the new norm.