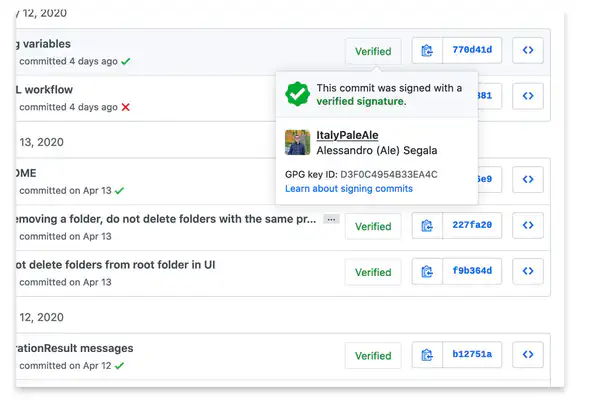

Even if you don’t know about signed Git commits, you might have seen this on GitHub:

Let’s leave everything else aside from a moment… isn’t it oddly satisfying to have a large, green “Verified” badge on your work? 😎

Making a commit “verified”, or to be more precise, signed, is not as hard as you might think. Just as it sounds, signed commits are …well, signed, cryptographically using a GPG key.

Why to sign Git commits

Before we get into the how, let’s talk for a moment about why you should sign your Git commits. Besides the desire to get that green, “Verified” badge on your work on GitHub, there are some concrete benefits.

When you commit a change with Git, it accepts as author whatever value you want. This means you could claim to be whoever you want when you create a commit.

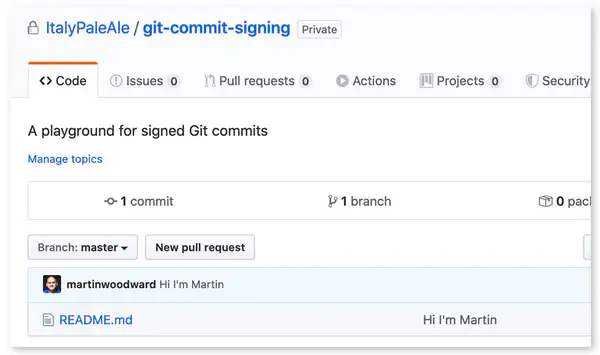

For example, here’s a repo I just created. As you can see, my esteemed colleague and friend @MartinWoodward from GitHub committed in it right away:

There’s only one problem: Martin did not do that; I did.

To make GitHub (and everyone) believe that Martin authored that really terrible commit, I just had to run git config user.name and git config user.email with values that match Martin’s. Those are not hard to get at all: it only took me one minute to clone one of his repos then run git log in it.

From the point of view of Git, this is actually working as intended. The committer details are designed just to identify who of your collaborators made a change, and are not meant to be used for authenticating people. Being able to impersonate other committers does not introduce a vulnerability per se. For example, just by setting my user.name to Martin’s, I do not get the ability to push code to his repositories: GitHub would require me to authenticate with his credentials before I could do that.

However, while this is not a security vulnerability per se, it can cause other issues. When you see an unsigned commit, you have no guarantee that:

- The author is really the person whose name is on the commit

- The code change you see is really what the author wrote (i.e. it’s not been tampered with)

Making a habit of signing your Git commits, instead, gives you the ability to prove that you were the author of a specific code change. It also gives you the ability to ensure that no one can modify your commit (or its metadata, such as the time you claimed that was made at) in the future.

The more sensitive the code you’re working on (e.g. things related to security, or mission-critical applications), the more you should pay attention. Attacks on the software supply chain are getting more common, and their potential consequences more dangerous. The FBI has warned us.

Here’s how two hypothetical attacks on the software supply chain could look like, with unsigned commits. First, imagine the case of a disgruntled employee who might purposely want to introduce a backdoor into an app they’re working on (on a repo they already have write access to), so they impersonate one of their teammates when submitting the code to keep the blame away from them.

Another example is someone creating a malicious pull request in an open source project and they make it look like someone else, for example someone with a great reputation, co-authored it, to make it more likely that the PR be accepted (if you maintain open source libraries, you know how time-consuming it could be to fully, thoroughly review every PR).

Please note that just because you sign your Git commits, it doesn’t stop others from impersonating you. I have been regularly signing my commits for about a year, but you could still make a code change and put my name on it. There’s no way I can stop you from doing that. However, whoever reads your code won’t see my digital signature (or the “Verified” badge), and so they at least have the ability to question the authenticity of that commit or its integrity. On the other hand, people who do follow my repositories can see that I’ve authored all the commits in the last year.

For your own projects, if your Git hosting service allows that, you can also require with a policy that all commits must be signed. On GitHub, that’s done with protected branches.

Cryptographic signatures and GPG

If you’ve never heard of cryptographic signatures or GPG, this brief, simplified explanation might help you.

Asymmetric cryptography

You might have heard that there are two main kinds of cryptographic algorithms: symmetric and asymmetric ones. Symmetric cryptography is the most understood one: first you encrypt your data using a passphrase, and then you use the same passphrase to decrypt the message and get it in clear-text again. If you want to share the encrypted data with another person, you need to give them the passphrase too. This is how algorithms like AES work, conceptually.

Asymmetric cryptography uses two separate keys: a public key and a secret (or private) one. As their names suggest, while the secret key must be protected at all cost, the public one can (and as will be our case later on, must) be shared with the world. With asymmetric cryptography, you encrypt a message using your public key, and then decrypt it using the private one. If you wanted to share an encrypted message with your friend, you’d use your friend’s public key to encrypt it. Your friend could then use their own private key to decrypt and read your message. Algorithms like RSA or the various elliptic curves work this way. Despite being lesser-known among the general public, asymmetric cryptography is wildly used, and it’s what makes TLS used by HTTPS possible too, among other things.

In addition to encrypting data, asymmetric cryptography can also be used to sign messages (and verify signatures). This works the opposite way: you sign a message using your private key, and others can verify the signature using your public key.

About signatures

When you sign a message, you’re adding a cryptographically-strong proof that you (or someone in possessesion of your private key) wrote that, and that the message was not tampered with.

For example, let’s say that you want to send a message to your friend saying “You and I will meet tomorrow at 11.30am”. You want your friend to be 100% sure that the message came from you, and you want to make sure that no one can change its content (e.g. changing from 11.30am to 1pm). You can do that by adding a cryptographic signature to the message.

To do that you have to do two things in principle:

- You calculate a hash (or checksum) of your message. You can use a hashing function such as SHA-256. As you know, hashing functions are one-way operations that generate a unique set of bytes from each message, and they cannot be reversed. The hex-encoded SHA-256 digest of “You and I will meet tomorrow at 11.30am” is:

579c4547d8dec2c4513de8c858a490a8a2679db205a0b3471f81d5b129d29b88. If you changed even just 1 bit in the original message (e.g. change the time to 11.31am), the final digest would be completely different (try it). - You use your private key to sign the calculated hash, using algorithms like RSA.

You can now send the signature together with the clear-text message, and your friend will have no doubt that you were the one writing those precise words.

Note that signatures are added to clear-text messages. Signing a message alone does not encrypt it! So, anyone could still read your original message, and could see that you signed it. It is possible to use RSA to both sign and encrypt a message, and that’s what’s called “authenticated encryption”, but that’s besides the scope of this article.

GPG: The GNU Privacy Guard

By now, I hope you at least have a general understanding of the idea behind asymmetric cryptography. Let’s see how we can use it.

The OpenPGP standard contains specifications on algorithms, encodings, etc, for real-world usage of solutions based on cryptography. Among the various implementations of the OpenPGP standard, the most widely-adopted one is likely GPG (also known as GnuPG). This is a free, open source (libre) application that works on Windows, macOS, and Linux, as a command-line tool. Countless tools and applications depend on GPG (or the standards it use) to deal with cryptography in a standardized, interoperable way.

One of the (many) things GPG does is giving you the ability to sign arbitrary messages or files. This works great with Git, and we’ll see how in just a moment.

GPG is a really large tool, with a lot of different functionality, and just like many things that are related to cryptography, it can get very complicated, very fast. Personally, I have been dealing with GPG for various reasons for years, and I still have a partial understanding of how it works. However, the good news is that signing Git commits is a relatively simple operation, and after you set GPG up, you’ll be able to forget it.

In addition to being a command-line tool, GPG also has a standard for distributing public keys. Remember how I wrote that the public key not only can, but often needs to be distributed to the world? Public keys are identified by an ID, and map to a person email address(es), including the ones used by GitHub.

For example, my pubic key’s ID is 0x30a525d4, which also maps to 43508+ItalyPaleAle@users.noreply.github.com. One of the sub-keys, 0x4b33ea4c is used for signing, and that’s what it’s used to sign my Git commits too.

Setting up our Git to sign commits

Ok, we’re finally ready to get started.

Installing GPG

Besides Git, the only requirement is that you must have GPG installed. I recommend using GPG version 2.2 or higher

- On Windows, you can download the Gpg4win distribution from the GPG website

- On macOS, the easiest thing is to use Homebrew:

brew install gpg - Most Linux distributions come with GPG pre-installed; if not, you can always find it on their official repositories.

Note that in some Linux distributions, the application is called

gpg2, so you might need to replacegpgwithgpg2in the commands below. In this case, you might also need to rungit config --global gpg.program $(which gpg2).

For macOS only

On macOS, you might also want to install a graphical pinentry application with brew install pinentry-mac, then add this line to ~/.gnupg/gpg-agent.conf (if the file doesn’t exist, create it):

pinentry-program /usr/local/bin/pinentry-mac

Additional configuration for Linux and macOS

On Linux and macOS, you can enable the GPG agent to avoid having to type the secret key’s password every time. To do that, add this line to ~/.gnupg/gpg.conf (if the file doesn’t exist, create it):

# Enable gpg to use the gpg-agent

use-agent

You will also need to add these two lines to your profile file (~/.bashrc, ~/.bash_profile, ~/.zprofile, or wherever appropriate), then re-launch your shell (or run source ~/.bashrc or similar):

export GPG_TTY=$(tty)

gpgconf --launch gpg-agent

Generate a GPG key pair

To start, generate a new GPG key pair (public and private):

gpg --full-gen-key

Configure the key with:

- Kind of key: type

4for(4) RSA (sign only) - Keysize:

4096 - Expiration: choose a reasonable value, for example

2yfor 2 years (it can be renewed)

Then answer a few questions:

- Your real name. You could use your GitHub username here if you’d like.

- Email address. If you plan to use this key for more than just Git, you might want to put your real email address. If it’s just for GitHub, you can use the

@users.noreply.github.comemail that GitHub generates for you: you can find it on the Email settings page.

You will be asked to type a passphrase which is used to encrypt your secret key on disk. This is important, otherwise attackers could steal your secret key, and then they’d be able to sign messages and Git commits pretending to be you.

You can verify your key was created with:

$ gpg --list-secret-keys --keyid-format SHORT

/root/.gnupg/pubring.kbx

------------------------

sec rsa4096/674CB45A 2020-05-16 [SC] [expires: 2022-05-16]

65B8A7455C949E73FC3B7330C16132F5674CB45A

uid [ultimate] ItalyPaleAle-demo <43508+ItalyPaleAle@users.noreply.github.com>

In the example above, my new key ID is rsa4096/674CB45A, or just 674CB45A.

You can confirm that GPG is working and able to sign messages with:

echo "hello world" | gpg --clearsign

If your GPG agent is having issues, you can restart it with:

gpgconf --kill gpg-agent gpgconf --launch gpg-agent

Adding multiple emails

You can add multiple email addresses by editing the key:

# Replace 674CB45A with your key ID

gpg --edit-key 674CB45A

In the GPG prompt, then type:

gpgp> adduid

Again, type the real name and the email address you want to add. To confirm, you’ll be asked to type the password to decrypt the private key.

Then, still in the GPG prompt, update the trust for the new identity:

# Use the number of the UID of the identity

gnupg> uid 2

gnupg> trust

# Type "5" (for "I trust ultimately")

Lastly, save and exit with:

gnupg> save

Configure Git to sign your commits

Once you have your private key, you can configure Git to sign your commits with that:

# Replace 674CB45A with your key ID

git config --global user.signingkey 674CB45A

Now, you can sign Git commits and tags with:

- Add the

-Sflag when creating a commit:git commit -S - Create a tag with

git tag -srather thangit tag -a

You can also tell Git to automatically sign all your commits:

git config --global commit.gpgSign true

git config --global tag.gpgSign true

Adding the GPG key to GitHub

In order for GitHub to accept your GPG key and show your commits as “verified”, you first need to ensure that the email address you use when committing a code change is both included in the GPG key and verified on GitHub.

To set what email address Git uses when creating a commit use:

git config --global user.email your@email.com

You can use your @users.noreply.github.com email (from the Email settings page on GitHub) or any other email address that is added to your GitHub account and verified (in the same settings page).

If it’s not already, that same email address must also be added to your GPG key, as per instructions above.

Once you’ve done it, upload your public GPG key to GitHub and associate it with your account. In the SSH and GPG Keys settings page, add a new GPG key and paste your public key, which you can get with:

# Replace 674CB45A with your key ID

gpg --armor --export 674CB45A

Your public GPG key begins with -----BEGIN PGP PUBLIC KEY BLOCK----- and ends with -----END PGP PUBLIC KEY BLOCK-----.

Making a signed commit

After configuring all of the above, your Git commits can now be signed with your GPG key:

# Add the -S flag if you did not configure Git to sign commits by default

git commit -a -m "Making my first signed commit"

You can check that the commit was signed with:

$ git log --show-signature -1

commit 8beed807e820d34cc7a35a0d69e9913bed7b1b03 (HEAD -> master)

gpg: Signature made Sun May 17 01:44:55 2020 UTC

gpg: using RSA key 674CB45A

gpg: Good signature from "ItalyPaleAle-demo <43508+ItalyPaleAle@users.noreply.github.com>" [ultimate]

Author: ItalyPaleAle-demo <43508+ItalyPaleAle@users.noreply.github.com>

Date: Sun May 17 01:44:55 2020 +0000

Making my first signed commit

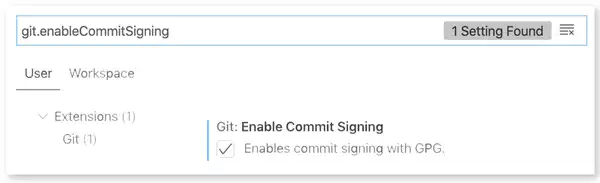

Configuring Visual Studio Code for signing commits

If you’re using VS Code, you can configure it to sign your Git commits with the Git: Enable commit signing flag (git.enableCommitSigning).

Using hardware tokens

Your GPG secret key is now stored (encrypted) in your GPG keyring inside your laptop. While this should provide enough protection for most users, it is still possible to export it, and thus steal it. Given that the key is encrypted with a passphrase, your key is as safe as the passphrase (choose it wisely!).

Additionally, having a private key in a file leaves open questions on how to (securely) back it up and possibly sync it across multiple devices. This Q&A on Stack Exchange Information Security contains various ideas, although a bit dated. Services like Keybase can help storing your secret keys on a dedicated cloud service.

A safer alternative, however, is to use a hardware token, for example security keys such as a YubiKey. This is what I use too. Among the various technologies a YubiKey supports, it can store a GPG key in a secure enclave, from where it cannot be extracted.

Setting up a YubiKey for its various functions, including storing a GPG key (and using that for signing Git commits or for connecting to a SSH server), takes a bit of time. If you just got a YubiKey and want to know how to best set it up, I highly recommend this guide from @drduh published on GitHub.