In the fall of 2007, my parents gave me an unforgettable gift for my sixteenth birthday: a first-generation iPhone.

I still clearly remember watching the keynote in which Steve Jobs announced the first Apple-branded phone a few months earlier. As a teenager attending high school in my hometown of Vicenza, Italy, I tuned into the livestream just before dinner, carefully listening to every word he said. That evening, Jobs started announcing a “widescreen iPod with touch controls”, a “revolutionary mobile phone” and a “breakthrough Internet communications device”–theatrically pausing before confessing that he was actually talking about one single device: the iPhone. Thousands of miles away from me, you could hear attendees exploding cheerfully through the live feed. Jobs went on demoing this amazing invention that, a decade later, would end up changing much more than the mobile phones market: it directly or indirectly impacted our society through mobile web, app stores, changing work-life balance, and social media.

October came, and so did the day I finally got my iPhone. I was really excited as I was the first one in my social circle with one. Every other teenager (and adult!) that saw my phone reacted in awe and with lots of curiosity. More than a few were also secretly envious, something I secretly did not mind. To add to the novelty, at the time the iPhone was only available for sale in the US.

To get an iPhone for me, my father had to ask a friend traveling to New York on a business trip to bring one back on the plane with her. That was not the end of it, however, as all phones were locked to the AT&T network. In order for me to be able to use my iPhone in Italy, I had to unlock it.

That process required learning a variety of tools and techniques developed by hackers in the community, then documented in various blogs and forums. The first step was to jailbreak the phone, which gave you full access to the system and allowed you to run third-party apps. Then you’d have add one of those “hacking” apps to your phone, which patched the bootloader to remove the lock the US carrier had put on it. Despite sounding like a mouthful, the iPhone hacking community had worked hard on the User Experience (UX), making this entire process relatively easy for most people with basic tech skills.

I really loved my shiny, new iPhone, and I was so excited about it that I was willing to accept many of its original limitations. It only supported slow 2G networks, didn’t have copy/paste, couldn’t transfer files via Bluetooth to my friends, and famously didn’t support Adobe Flash, which was ubiquitous on the web at the time.

However, there was one thing I really couldn’t stand: the Messages application could only store 1,000 texts (SMS).

That was 2007 — before the days of WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, Telegram, etc. Instant messaging was something people did on their PCs only, with things like Windows Live Messenger (née MSN Messenger) or AIM.

For a high schooler like me, text messaging was the main way I kept in touch with my friends daily (what was I supposed to do, call them?). With my carrier giving me a whopping 100 free texts per day (seriously, we had to pay for them), between sent and received texts it would take less than a week to reach the storage limit of 1,000.

That’s when it all started.

Because my iPhone was already “hacked” (jailbroken), as a requirement for unlocking it and use it in Italy, I had full system access already. That allowed me to c extract any document I wanted, including my phone’s text message database.

It wasn’t even a month since I got my iPhone that I had already built a small “app” running on my laptop to archive my text messages forever. I would manually extract the SMS database from my iPhone, copy it to my laptop, then use a set of scripts written in PHP (the only programming language I knew at the time) to store the messages in a local database, and finally display them using a web-based interface.

This thing I put together worked just fine for me, but I immediately realized the “business potential” of what I had just created. Just like myself, I assumed many others had the same annoyance. I could have used what I learned to help them too, and maybe make some pocket change in the process. As a matter of fact, I did consider myself an enterprising teenager.

The idea had potential, and the “app” I built for myself already provided solid foundations, so I just needed to do a bit more work to turn it into a commercially-viable project.

The biggest challenge was making the solution more accessible to others, including those who were not particularly tech-savvy. That’s when I started learning about app development for iPhone.

Famously, Apple did not want the iPhone to support third-party apps at the beginning, saying developers should build web apps instead. That policy didn’t last long, and with the iPhone OS 2 update, launched in mid-2008, the official App Store came to life: the rest, as they say, is history.

However, the hacking community had already found a way to sideload apps and had even developed an “app store” called Cydia where you could find games, apps, and even mods to enhance the capabilities of the operating system itself. Cydia came preinstalled on every jailbroken iPhone, which meant potentially hundreds of thousands of people had access to it.

Everyone could build apps that would be published on Cydia, as long as you knew how to–something that was not remotely as easy to do as it is with today’s tools. As an enterprising teenager with quite a bit of free time on my hand during those winter afternoons and evenings, I took on that challenge.

The first version of YouArchive.It came out in January 2008.

Today, you would describe YouArchive.It as a cloud service to store iPhone text messages. You could store all your messages in there, then read and search them using a web-based application.

There’s still a video left on YouTube showing the application in action (this was the third, and last, version):

With YouArchive.It came an iPhone application too. Published on the Cydia app store, it allowed importing messages into the “cloud service” directly from the phone.

YouArchive.It was free to use with a limit of 80,000 text messages. Because personal communications can be sensitive, all messages were stored encrypted. With a one-time payment of just €5 (about $6), you could become a VIP, remove any limit and enjoy unlimited storage.

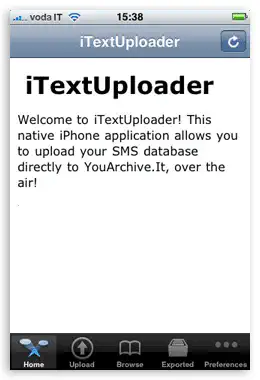

A screenshot of iTextUploader running on a first-generation iPhone

For the next year and a half, YouArchive.It continued to grow organically. A few blogs and websites dedicated to iPhone “hacking” and to the underground app stores wrote about the app. Even a small radio program in the US featured it

I continued developing the app as a side project while in high school. I was also providing tech support and maintaining the infrastructure.

Listening to users’ feedback, I would periodically add new features. YouArchive.It started displaying emojis as soon as the iPhone supported that (outside of Japan, it required downloading an app to enable them). Users asked for and got the ability to restore texts in another iPhone, before iCloud was available. I also implemented other privacy features such as requiring a password to open the mobile app.

What I didn’t realize at the time, however, is that I had, unknowingly and unwillingly, built a spying tool, and a really convenient and efficient one.

Enough users were paying the fee to become VIP that I could cover the costs of running the service–this was before everyone was using Amazon Web Services or Microsoft Azure, so I was renting a co-located physical server which wasn’t cheap–and keep some pocket cash. Not much, but enough to pay for some hobbies and outings with friends.

Most importantly, building YouArchive.It gave me a lot of satisfaction and the opportunity to learn a lot of things about software development, business, dealing with customers and listening to their feedback.

When I finally shut the service down, in June 2010, YouArchive.It had about 32,000 registered users who stored over 76 million messages.

The first, and stated, reason for the deprecation was a technical one: YouArchive.It’s iPhone app required using private APIs, which meant it could not be published on the App Store (and it still couldn’t to this day), limiting it to jailbroken phones only.

The second reason however was the most important to me, even though I have not revealed it until now.

About a year before the app closed, in April 2009 I implemented a new feature that was requested by many users: the ability to upload texts automatically, in background, without user intervention. For paying “VIP” users only, the mobile app could automatically send all new text messages to YouArchive.It, as often as every 15 minutes.

Automatic upload was an incredible convenience for many users that wanted to hoard their texts like me, to keep them forever, search within them, print or export them, or just liked having a backup.

What I didn’t realize at the time, however, is that I had, unknowingly and unwillingly, built a spying tool, and a really convenient and efficient one.

Thanks to background uploads, people could install the YouArchive.It app on another person’s iPhone, set it up, maybe even hide it (something possible on a jailbroken iPhone), and then watch as the text messages come in, almost real-time. Jealous partners, stalkers and the likes could install this tool on an unknowing victim’s phone with relative ease.

I can’t remember how I discovered that — it might have been a support request from a user or a post in a bulletin board. I also can’t know how many people were using YouArchive.It for their own archiving rather than to spy on others. Realizing what my users were doing, however, made me feel really uncomfortable and I did not want any part of that anymore.

As a senior in high school, barely eighteen years-old, I realized for the first time how technology can have a dark side, and how it’s often in our hands, as developers or other creators of technological solutions, to account for unintended consequences.

They say that software is eating the world. That was how Marc Andreessen started his famous essay in 2011, and as we read this nine years later, it is something that should resonate with most people.

If you never read it, or if you haven’t read it recently, I recommend you pick up Andreessen’s article now. Written in one of the most flourishing times for technology, it is an ode to the utterly enthusiastic and optimistic culture that was shaping Silicon Valley and that brought us the tech giants on which we depend on daily: Google, Facebook, Uber, Twitter, Apple, etc (some of these companies had been around for decades, but started expanding significantly again during those years). In Andreessen’s mind, just like in the minds of many others in the same environment and time, a software-controlled future was not only happening and imminent (as history proved him right), but also idyllic. Technology was to be the great force that solved all of the world’s problems, and Silicon Valley was to be the place where that would begin.

As tech companies were “moving fast and breaking things” while working towards “making the world a better place”, they were disregarding the potential side effects of their innovations. Just like me when I created my text message archival app, they failed to consider how their products and services could be misused by some individuals, or negatively impact groups of people, or even cause large-scale socioeconomic shifts.

Perhaps few examples of how unintended consequences caused harm to real people, sometimes even up to death are as strong as what we see with social media.

There are already countless essays arguing how companies like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter have failed us all, us humans, and have invoked for them to be shut down; this article isn’t one of them. I do think that generally social media has the potential to do good things: personally, I appreciate how Facebook and Instagram let me keep in touch with my family in another continent.

I have no doubt that the people building those platforms are good people, with positive intentions. If anything, their only sin is an excess of optimism and trust in the fact that humans always have the best intentions at heart. While that’s true for most of the people, most of the time, sadly it isn’t always the case.

The “like” button, in its various declinations, was meant as a fun way to engage with content our friends posted online. Its unintended consequences included creating a world in which everyone is compelled to always portray themselves under the best possible light, and living a life full of beautiful objects, exotic trips, intriguing adventures. These fun distractions turn into comparing our own life with what we perceive as other people’s perfect existences and make us feel anxious and depressed.

To start, we need to abandon the assumption that technological innovation is always, necessarily good.

On social media, people tend to create “echo chambers”, in which people surround themselves only with those who think alike. This causes increased ideological polarization, with consequent political destabilization of societies, as well as more unhappiness. Facebook’s solution to the privacy scandals of 2016, including the Cambridge Analytica situation, was to double-down on their groups feature, which are just amplifying reinforcement biases and polarization of thinking.

One of the biggest virtues of social media is their ability to support free speech. A constitutionally-protected right in every country around the world, at least in democratic ones, its defense is a noble cause. However, they also provided a platform to spread misinformation, foreign state-sponsored propaganda, disproved conspiracy theories, and lies that can be outright harmful to people, such as false and unproven medical treatment. Italian writer, philosopher, and Nobel Prize laureate Umberto Eco famously called social media “the invasion of the idiots”.

What’s worse is that the algorithms that control what we see on websites like Facebook and YouTube feed us with content that is more and more extreme and polarizing and provide free amplification to a lot of harmful content. Those algorithms were designed to recommend content based on what users seem to enjoy consuming, with the ultimate goal of driving more user engagement: if you watch lots of aviation-related videos, you’ll see more stuff about airplanes; likewise, if you follow lifestyle bloggers/vloggers, you’ll see more of that content. However, over time certain actors mastered techniques to game the way algorithms work, and push content to users that drives their own agenda; a clear example is RT, or Russia Today, a channel affiliated with the Russian government that spreads misinformation and conspiracy theories on YouTube.

It does not have to be as grim as it looks.

In fact, there’s a lot that the people who are creating new things can do: software developers, product managers, inventors, startup founders, hobbyists… Everyone who is driving the innovation can, and should, take action to ensure that technology has a positive impact on the world, not just on average but at a wholesome.

To start, we need to abandon the assumption that technological innovation is always, necessarily good.

Just because something can be built, it doesn’t mean it should be built. We should begin by stopping and considering how the innovation we are working on could be misused, or how it could come with negative externalities. This is an exercise that software developers tend to be naturally good at, given that considering every possible scenario and every what-if’s around something is a necessity when writing code. A healthy amount of cynicism could be helpful in this case: starting with the assumption that if something could be misused, then it will be misused by some people.

Sometimes the potential for abuse is rather clear, or it should be. The creators of the anonymous messaging app Yik Yak, which for a bit was all the rage on college campuses, should have seen the wave of bullying and harassment coming. Likewise, it should have been fairly clear how the people-rating app Peeple was going to be misused, even by those who did not watch Black Mirror.

Sometimes, instead, the potential for abuse more subdued, and careful thinking and planning is required to account for all unintended consequences. These are the situations in which “moving fast and breaking things” is actually your enemy. This way of working, the norm in many Venture Capital-funded startups, often causes creators to put growth before everything, and is the opposite of adopting a responsible amount of mindfulness.

Instead, you should instead validate your idea, discuss it with others, and while testing prototypes, define meaningful KPI’s (Key Performance Indicators) that look at the impact outside of your business goals too. For example, if the sole KPI is user engagement, you could end up writing algorithms that promote polarizing content which tends to be more addicting, but not necessarily positive for the society.

Of course, there will be cases in which we’ll miss things, as hindsight only works backwards. To limit damage and prevent problems from spreading further than needed, creators should periodically re-assess how their solution is having an impact in the broadest sense. Keeping a humble and open mind, or in other terms assuming a “growth mindset”, helps continuously learning and finding surprising things. With constant learning, it’s possible to identify opportunities to course-correct and resolve the issues, real or potential, that could lead to our creations to be misused.

Sometimes that involve simple design changes, for example aimed at making users more in control: looking back, I could have limited the possibility of using my app from ten years ago as a spying tool by displaying a notification every time text messages were being uploaded. Recognizing how much of a cesspool the YouTube comment section can be, Google tried to force people to use real names when commenting on videos in 2013, but quickly reverted the change after facing significant backlash–possibly because the move was designed more as an imposition of their ill-fated Google+ social network than something to actually help the community grow healthier.

However, in other situations doing the most ethical thing might require taking painful actions too, such as pivoting an idea or shutting something down entirely. On this subject, the final episode of HBO’s Silicon Valley show was beautiful, by the way–but I won’t spoil it for you any more than this!

Thankfully, the topic of ethics is getting more and more relevant in software development, and it’s now something that’s taught in college campuses too. We need a new generation of creators that are more attentive to the issues that technology can cause, and not just those it can solve; this includes being more cautious and carefully account for unintended consequences.

The conversation is also getting more mainstream, as individuals are starting to keep tech companies more accountable for their actions. At the same time, governments are (slowly, but steadily) stepping in to regulate those companies’ behavior when they believe society is being harmed: examples include protection of labor and privacy rights.

Tech workers themselves are starting to wake up to the importance of their role, and are now speaking out, with ever-increasing frequency and passion. Employees at companies like Google, Facebook, Microsoft, etc, have raised their voices and staged walkouts to demand their organizations to do better at all kinds of things that matter to them, including: promoting diversity and inclusion in their workplace and in the world, protecting human rights globally, protesting the sale of their technology to the military or other organizations perceived as unethical, etc.

These good changes are hopefully the start of something bigger, a moment in which every creator is putting ethical considerations up and front.

At the end of the day, in fact, we are all just working to make the world a better place.